Air of Authority - A History of RAF Organisation

No 43 Group and the Civilian Repair Organisation

The following is extracted from Chapter 5, AP3397 'Maintenance' (AHB - 1954)

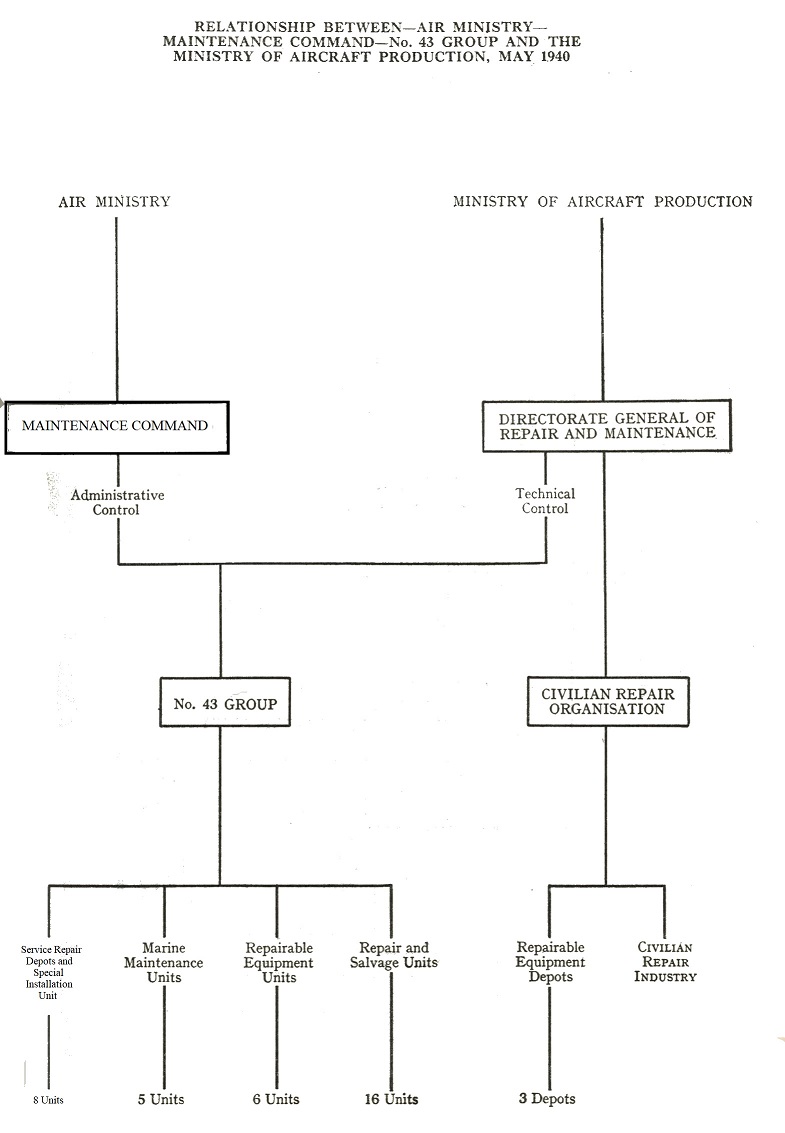

The Transfer of Technical Control to the Ministry of Aircraft Production

With the formation of the Ministry of Aircraft Production in May 1940, the technical control of No 43 Group passed from Maintenance Command to the new Ministry. The administration of the Group, however, by Air Ministry. continued as before, through normal Maintenance Command channels.'

Movement of HQ, No 43 Group to Oxford

In October 1940 it was decided, after consultations with MAP, to move the Headquarters of the Group salvage organisation from Andover to Oxford. The section was in future to be known as No 43 Group (Salvage) and was to be responsible for its operational control, issuing block allocations of repair capacity of all types of aircraft to the salvage centres. A civilian was appointed, responsible to MAP, to co-ordinate the salvage work of the Group with the requirements of CRO and any other bodies interested in salvage.

Temporary accommodation at Oxford was at the Morris Motor Works, Cowley, to which the transfer was made on 16 October 1940, a further move being made to Merton College, Oxford, on 5 November 1940.

On 1 February 1941, HQ, No 43 Group also moved to Oxford, accommodation' having been secured at Magdalen College. The HQ, No 43 Group (Salvage) was now merged into the one Headquarters, which was henceforward known as Headquarters, No 43 Group.

The Expansion of No 43 Group, 1940-1944

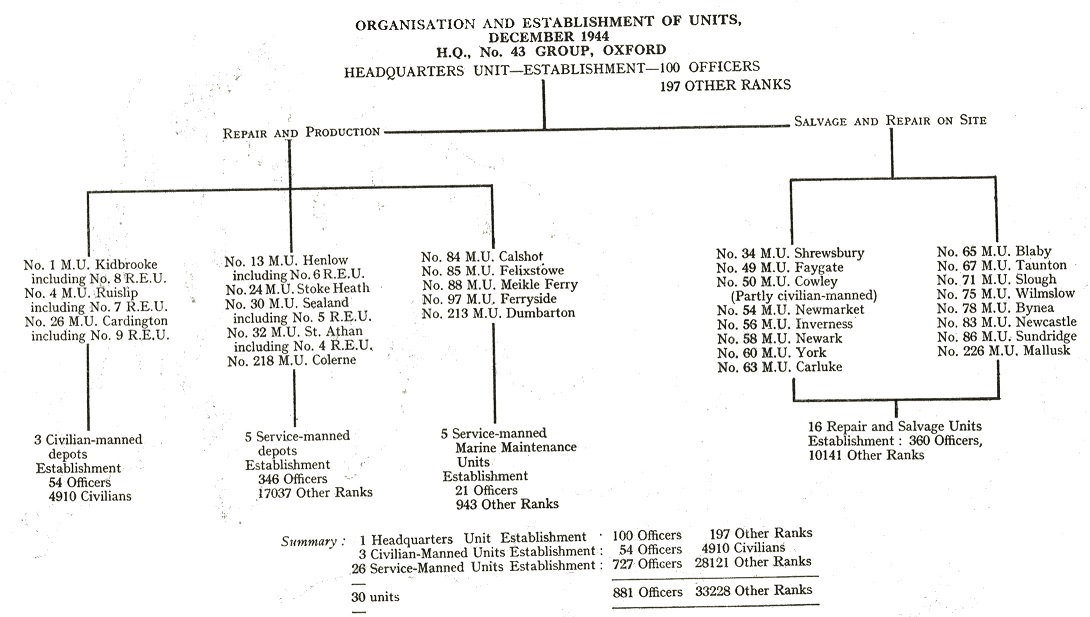

The expansion of the Group really started in October 1940, when there were 15 units with approximately 13,700 personnel. By March 1942 this had risen 29 units and 26,000 personnel, with a planned expansion for that year to 30 units and 30,500 personnel. This increase consisted, of one small Aircraft Depot, seven Repair and Salvage Units, six Marine Repair Units, and an enlargement of existing units generally.

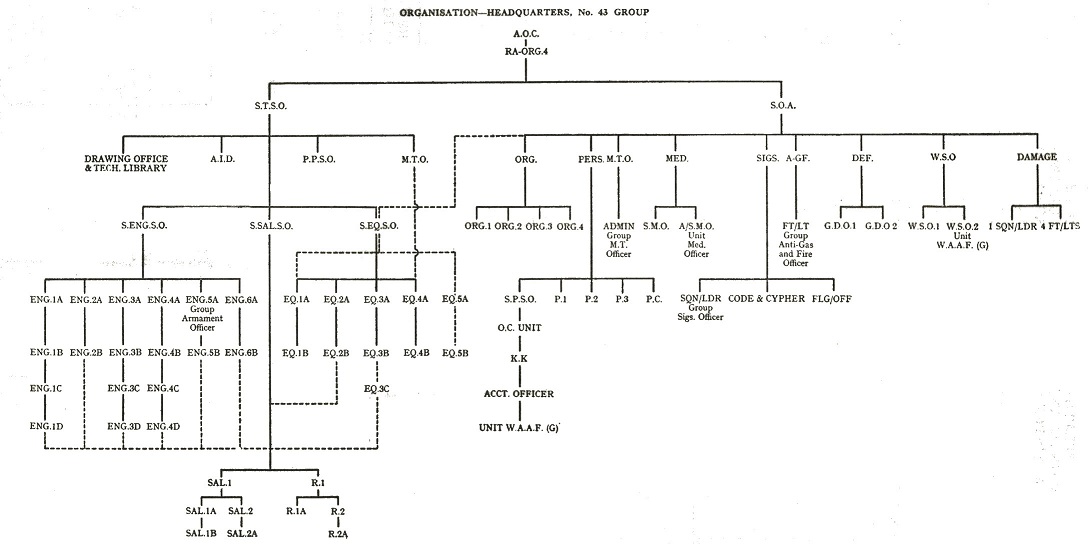

The AOC, No 43 Group submitted a paper on this expansion to the Director of Repair and Maintenance on 2 April 1942. This gave units and their Establishments together with the comparative repair output figures of principal items for two 13-week periods, October/December 1940 and October/December 1941. It also showed that during this period the increase in HQ Staff Officers had been at a much lower ratio. Details of the proposed HQ Establishment were submitted to the DRM on 19 April 1942. The main differences as regards organisation were in the addition of a Senior Technical Staff Officer with the rank of Air Commodore to be responsible for the Salvage Branch, which had now become Repair and Salvage; and the placing of the Equipment Staff under the STSO. The main increases asked for in establishment were in the Equipment Branch, but there were several requests for upgradings of posts to meet the increased responsibilities brought about by the expansion, including that of the AOC from Air Commodore to Air Vice-Marshal.

Summary of the Group's Functions in 1944

With the growth of the operational Commands the Group's commitments continued to increase both in number and volume until the peak year of effort was reached in 1944. At this stage the functions and activities of No 43 Group may be summarised into the following two broad divisions: -

(a) Repair of all kinds, as well as manufacture, modification, installation and development work at the Service Repair Depots, together with certain more specialised work, such as repair of marine craft

(b) Salvage of aircraft and repair on site of Category 'AC' aircraft

|

| Diagram 5 |

|

| Diagram 6 |

|

| Diagram 7 |

|

| Diagram 8 |

Repair and Production, 1944

Although Service Repair Depots and Marine Maintenance Units provided repair and production facilities similar in many cases to those of civilian firms, one very considerable difference existed, namely, that No 43 Group repair units were required to undertake work which, either because of its being in an early stage of development or part of an unstable programme, rendered difficult the setting up of a production flow and could not be accepted by the aircraft industry. The allocation of such programmes to Service repair capacity meant that this organisation had to remain completely versatile and flexible. This flexibility enabled commitments to be undertaken at very short notice; for example, during 1944 parties were sent on a number of occasions to aircraft civilian contractors to clear bottlenecks in production; other parties were sent to assist operational Commands in maintaining aircraft serviceability in the field during intensive operational periods, and similarly to speed up urgent modification work.

In addition, the organisation provided capacity for work which could not be given to civilian industry due to such overriding factors as security or urgency. This was particularly true of the development of radar and radio, and in this respect it is no exaggeration to say that the operational formations worked with the No 43 Group organisation at their elbows.

The organisation included seven Repair Depots, one Radar installation and five Marine Craft Repair Units and employed some 18,000 technical personnel, the total strength of these thirteen units being equal to about two modern Army divisions. Workshop accommodation alone comprised some 2,700,000 sq ft, and included airframe, aero-engine, and accessory repair shops, shipyards, motor transport repair shops, foundries and machine shops, instrument repairs, manufacture and fitting sections, armament repair sections, radio manufacture, repair and fitting shops, oxygen apparatus development, production and repair shops and specialist equipment development and servicing.

The work carried out included major repair, modification and reconditioning of aircraft, marine craft, motor transport vehicles, engines, radio, armament, electrics and instruments. In addition the complete manufacture of a wide range of equipment was undertaken as well as extensive radar and instrument installation programmes for operational Command aircraft There were, infact, few classes of items in the whole extensive range of RAF technical equipment whose repair, modification or manufacture was not undertaken within the No 43 Group repair and production organisation.

Bulk statements of output in terms of manufacture convey little meaning as production ranged from repetition work running into thousands per week of a single item, to major overhauls involving thousands of man-hours as in the case of a Lancaster aircraft Some indication, however, of a year's production output may be gained when it is visualised as being equivalent in man-hours to the complete overhaul of 40,000 Merlin aero-engines per annum.

The record which follows this brief summary has been divided into sections according to their broad functional aspects and is not therefore directly related o the detailed organisation of No 43 Group.

a) Aircraft

No 43 Group repair depots dealt with major repairs to specified types of aircraft whose repair was beyond unit or No 43 Group repair-on-site capacity. The work was carried out in the airframe repair shops of the four aircraft repairing depots and amounted in many cases to completely rebuilding the aircraft concerned. In addition, extensive aircraft modification programmes were undertaken and assistance given to the aircraft industry and operational Commands.

During 1944 a total of 3,091 aircraft were dealt with by repair depot personnel, a further 331 being in course of progress at the end of the year. This showed a considerable increase over the total figures for 1943 of 983 aircraft

The repair of Lancaster aircraft formed the largest single commitment under is heading, each rebuild consuming upwards of 25,000 man-hours. The hundredth Lancaster was completed and returned to Bomber Command during the year. Other aircraft dealt with included Dakotas, Wellingtons, Typhoons, Mosquitos, Beaufighters and Mustangs. In addition, the repair of all Typhoon monocoques was met by the Group and 231 were repaired, fully modified and returned to Aircraft Equipment Depots during, the year.

A repair commitment typical of the close support given to the operational Commands may be instanced by reference to a short-term programme undertaken to meet an operational need. Prior to the liberation of NW Europe extensive sweeps by fighter aircraft were carried out. Aircraft damaged in these sweeps which were beyond unit repair, but which were still airworthy, were flown into No 43 Group units, repaired and returned to their respective squadrons with the minimum delay. In this way 28 aircraft, which under normal methods would have been non-operational for some time, were available to the Command at a time when every aircraft was needed to maintain maximum operational effort. .

Most of the aircraft capacity during 1944 was taken up by aircraft modification, and one aspect, namely, radar installation, assumed such proportions that it has been dealt with in a separate section;

A typical modification commitment was the conversion of 61 Wellingtons for special night reconnaissance duties to meet urgent 'D' Day requirements. The work involved the design and fitting of camera hatches, fitting of vertical cameras, structural modifications to take cartridge dischargers, and the redesign and fitting of a new front turret. Another major modification commitment was that of converting Canadian-built Mosquitos to operational standard. These aircraft were ferried across the Atlantic and delivered to a No 43 Group unit where they were stripped of their ferrying equipment, modified, and flight tested. The output for 1944 was 213 aircraft and the unit became an advisory centre for modification and repair of Canadian Mosquitos both for RAF formations and the Ministry of Aircraft Production.

Other modifications included the fitting of rocket projectors to 104 Typhoon aircraft, modification of 70 Spitfires to photographic reconnaissance standard, and modification of 155 sundry other aircraft flown into No 43 Group depots. Many of these modifications, and associate installation work, although in themselves comparatively straightforward, were complicated by the need to manufacture and, in many cases, design all or some of the fittings to be incorporated.

A total of 674 aircraft, exclusive of radar installations, were modified at repair depots during 1944.

During the same period 52 technical parties, consisting of some 800 personnel, were attached to various RAF formations and civilian factories in order to supplement their capacity during critical periods or to carry out modifications which were beyond squadron facilities. This work varied in character, the largest single commitment being the modification of 1,550 Halifax aircraft for Bomber Command.

When the flying bomb attack on this country was at its peak, Headquarters, Air Defence of Great Britain asked for, and received, urgent assistance from No 43 Group in their venture to modify the engines of 30 Mustang aircraft in order to raise their top speed. This task was completed by the Group in 8 days. In this connection working parties also visited various Servicing Echelons to assist in improving the surface finish of aircraft, thus increasing their top speed by some 7 or 8 miles per hour.

A total of 1,733 aircraft, again exclusive of radar installations, were modified on site during 1944.

Work carried out by No 43 Group parties detached to civilian contractors included: the clearing of congestion on the Mosquito final production line at Messrs De Havilland, and flight testing and rectification of 197 Mosquito aircraft from the De Havilland factory; setting up at Messrs Hawksley's aircraft factory a RAF production line to increase the output of Albemarle aircraft required for glider-towing on Continental operations; the attachment of RAF tradesmen to aircraft firms when their civilian counterparts were not available.

(b) Engines (Aero, Marine and MT), Propellers and Aero-Engine Accessories

Whilst engine repair in No 43 Group covered the three above sub-divisions, all of which had much in common, the magnitude of the task in each case was so disproportioned that the three types must be regarded separately.

The 1944 aero-engine repair programme included the complete overhaul of the Rolls Royce Merlin types 20, 22 and 24, and the Bristol Hercules XVI, the Bristol Pegasus XVIII and the American engines, Allison F3R, Pratt and Witney Twin and Double Wasps.

Complete overhaul consisted of entirely dismantling the engine, after which the components were subjected to detailed inspection, all parts being categorised either serviceable, repairable or scrap. The reconditioning process included the grinding and honing of sleeves of cylinder bores as appropriate and the replacement of excessive wear at the top of cylinder bores by the building up of hard chrome plating; similarly, bearings were remetaled, or in the case of lead bronze bearings scraped and lead-plated anew, crankshafts were ground and lapped. All parts of the engine subject to wear received attention, numerous processes being involved; hard chrome plating was used to face a variety of parts such as rocker pads; valves and valve seats were re-cut and ground, and re-bushing, re-turning or resurfacing of worn parts took place. During and after reassembly engines were submitted to full AID inspection after which they were removed to test bays where, after a running-in period of four to five hours, they were tested under full power and simulated high altitude conditions.

The overhaul of American engines presented a particular problem as no parent firm existed in this country. No 43 Group assumed this responsibility and acted as a source of technical information. They also provided technical investigation facilities similar to those which would have normally been supplied the civilian contractors.

The man-hours involved in complete aero-engine overhaul varied to some extent, but the Merlin and Twin Wasp which took 900 and 1,000 man-hours respectively may be regarded as typical. These figures included man-hours occupied in preliminary as well as AID. inspection, and test, and also the technical effort contributed by other sections of the unit such as the general engineering section.

The total number of aero-engines overhauled during 1944 was 4,695 and would have been greater but for policy changes which introduced more advanced types. The figures for 1942 and 1943 were 2,774 and 4,298 respectively.

The complete overhaul of both British and American aero-engine accessories was carried out at five units. The output during 1944, exclusive of electrical accessories which are dealt with in Section (e), exceeded 60,000 items.

The main capacity within the Group for the repair of both wooden and metal propellers was centralised at No 24 Maintenance Unit. As the unit was extremely well equipped they were able to undertake the complete overhaul of most types of Rotol and De Havifiand propellers. The unit was also able to carry out major repairs to metal blades as it possessed the equipment for heat treating and reshaping, anodising, shot-blasting and dyeing.

Due to a change in policy the output of completely overhauled propellers was well below the shop capacity and amounted to only 385 propellers; output of propeller blades was, however, 4,576. The repair methods for wooden blades greatly improved during the war years and major repairs were carried out on blades which formerly would have been regarded as useless.

Another aspect of propeller repair was the reclamation of hub parts and blades from propellers which were beyond economical repair. These were fed into the MAP organisation and used in the building of new and repaired propellers; blades with broken tips were usually reshaped to smaller dimensions and converted to another type for which they were suitable.

Marine engine repair within the Group again was varied in character but certain types predominated, notably the Napier Sea Lion, the Ford 8 Marine and the Meadows 100 HP and 8/28. In all, 793 marine engines were completely overhauled during 1944, and the procedure for complete overhaul followed closely that which was carried out for aero-engines. Complete overhaul of accessories, such as Parson, Thornycroft, and Vosper reverse gears, various marine auxiliary engine generator sets and similar equipment, was also carried out.

The importance of maintaining stocks of overhauled marine engines to cover the liberation of NW Europe was recognised early in the year. Owing to a shortage of spares this was subsequently found to be impossible, but, nevertheless, the output from repair was maintained, so that at no time during this critical period was any high-speed launch unserviceable due to non-availability of engines.

The major repair and overhaul of MT engines was carried out in MT repair shops and, to a small extent, to supplement marine engine input in one ERS. The overhaul procedure was similar again to that briefly described for aero-engines, the majority of such overhauls being carried out concurrently with the complete overhaul of the vehicle. A total of 274 engines were dealt with during 1944.

(c) Radio

Radar-W/T-Typex. Radio formed an important part of the No 43 Group repair and manufacture organisation, and during 1944 its growth was almost spectacular. In this sphere of activity the Group gave very close support to the operational Commands, handling the most urgent commitments where speed and secrecy were the overriding considerations. In this connection the preparations for 'D 'Day and radio countermeasures deserve pride of place. For repair and manufacture alone 28 officers and 957 other ranks of the appropriate radar or W/T trades were employed and the all up strength was 1,510, but, when visualising this capacity, it must be realised that the radio sections were backed up by other specialist capacity as required.

Radio commitments varied and included the repair of airborne and ground W/T, airborne Radar and Typex machines, the manufacture of radio countermeasures equipment, and then their appropriate test apparatus. It also covered the breakdown of obsolete W/T and radar equipment.

Radio repairs reached the total of 19,342 equipments during 1944 as compared with 11,030 in 1943, but these figures do not represent fully the extent of the expansion as the later equipment was much more complicated than that handled during the previous year. Equipment repaired consisted of the most modem communication and radar devices in use and included night bombing, night fighter and anti-submarine equipment. It became, in fact, the policy of DDRM (Radio) to adjust the national radio repair capacity so that the latest and most complicated equipment was dealt with in No 43 Group; often when the teething troubles had been ironed out and the priority downgraded, the commitments were re-allocated to civilian contractors to make way for the newer types.

The repair of airborne radar achieved the most striking advances, 11,200 equipments being dealt with in 1944 compared with 4,630 in 1943. This expansion occurred at a time when equipment was becoming increasingly more complicated, the number of types having increased from 5 in 1943 to 12 in 1944. The necessary organisation to deal with this ever-changing programme of radar repair was one of the outstanding achievements of the Group.

During the latter part of 1943 new radar devices were introduced in rapid succession and taxed civilian manufacturing capacity to the limit. In order to prevent any delay in the 'supply pipe line' at a time when operational squadrons required them on the highest priority, a system was devised by No 43 Group which became known as 'Crash Repair'. This may be defined as 'a system of repair in which speed of accomplishment took priority over all other considerations'.

In practice, a small 'float' of new equipment was given to the repairing unit, which was in touch with a central collecting point in each operational Group. Each collecting point was fed by squadrons with their unserviceable equipment which was collected daily by the No 43 Group repair unit, who at the same time delivered advanced replacements. Thus, no piece of equipment was out of service for more than 48 hours. This was equally true at the repair unit since the 'float' was necessarily so small that equipment had to be repaired on the day of receipt, a task which was increased by the fact that every radio repair, whether on a crash or normal basis, had to undergo full AID inspection and test before leaving the unit. Crash Repair was first introduced to deal with urgent arisings from Bomber Command but was later extended to other high priority equipment, and, during 1944, three completely different radar equipments were handled in this manner.

Radar repair was not limited to British equipment but covered some of the most complicated airborne American equipment which became a standard fitment on some types of British aircraft

The repair of W/T airborne and ground equipment was the most long-standing commitment of the Group so far as the signals branch was concerned; the policy being to repair equipment of current operational use. The growth of large-scale operations threw an increased amount of work on the depots which in turn was reflected in the number of equipments repaired. The changes in equipment from TR9s, T1082s and R1083s to TR1196, TR1133 and TR1143 necessitated an increasing amount of test gear of greater complexity. This in turn demanded a much higher degree of skill on the part of the wireless mechanic.

Woven into the pattern of radio repair were numerous manufacturing commitments which varied from the more or less routine production of test equipment to the manufacture, at exceedingly short notice, of countermeasure items to meet specific operations both at home and overseas.

Frequently radar or W/T equipment jobs were given to the Group on the grounds of speed alone as it had been proved on numerous occasions that the Group could undertake the manufacture of the most complicated equipment from sketches or a prototype in less time than that taken by civilian contractors; on one occasion equipment of the highest priority being delivered within three weeks of the requirements being known. This speed was made possible by the flexible and versatile radio organisation within the Group and the fact that it possessed almost unlimited engineering resources at units in the form of the general engineering sections. These enabled the entire equipment to be produced at a single unit, irrespective of whether it required metal work, welding, high precision fitting or turning, plating or other forms of finishing. While actual components were not normally manufactured, the Group was equipped for most types of windings and impregnations. It could also fabricate small items such as tag boards and components for sub-assemblies, chassis and dust covers and, if necessary, even transit cases. During 1944, 11,120 pieces of equipment were manufactured as compared with 5,800 manufactured in 1943.

Another important part of the capacity was taken up with the manufacture of Typex components for which at that time no capacity existed outside the Royal Air Force in view of the secrecy of this cypher machine.

Most of the No 43 Group depots dealing with radio commitments had associated radio breakdown sections, and one depot had a special function in this connection having a complete section devoted to it.

Radio breakdown involved a reduction to component parts of Radar and W/T equipment. The supply of components used for radio repair work was very scarce and although this equipment was obsolete or unrepairable as a whole, nevertheless it contained numerous items which could be used again. These, after AID inspection, were either fed back into No 40 Group units or else sent to operational or other formations, some being returned to civilian contractors, for the benefit of the Services at large.

(d) Special Installation

Radar. Radar installation was separated from the other radio or modification work in view of the proportions which this commitment assumed during the period under review. One unit was devoted entirely to aircraft installations and another had a section which also specialised in this work, whilst the installation and assembly of radar mobile convoys was dealt with at a third.

The two units which carried out aircraft radar installation were also responsible for retrospective installation on site by means of travelling parties. Altogether 3,509 aircraft had installations incorporated during 1944, 1,531 of which were carried out by travelling fitting parties. Over 3,000 of the kits for these installations were manufactured within the Group by the general engineering sections. Approximately 1,350 technical personnel were engaged on aircraft installation at the repair depots and an average of 150 personnel were on similar work at various operational airfields.

The reasons why it was necessary for these installations to be dealt with in No 43 Group were threefold. First, to fill the gap between the time aircraft were received unmodified from the contractors and the time of embodiment on the production line. This could vary from six to eighteen months and in fact some items were not incorporated during the period of hostilities. Secondly, to enable technical difficulties to be overcome, both in installation and test, before handing over to other formations for fitting as a normal modification. Thirdly, the development of radar became so rapid that it was necessary to introduce new modifications in 'mid-stream' in order to maintain or raise the performance to meet specific operational requirements. Such modifications had invariably to be prototyped and manufactured, entailing considerable development work. Full approval having been obtained for these prototypes, modification proceeded, often on a 'crash' programme basis.

These rapid developments in airborne radar increased the number of possible aircraft installations, and British radar often having its American counterpart still further complicated the situation. Quite often each equipment possessed certain functional advantages, and this led quite naturally to the operational Commands requesting the fitment of both types. Five or six major installations became commonplace, and in aircraft which had not been designed for such developments the problem of where to accommodate this additional equipment, in a manner in which it could be used and serviced, reached the point where the brackets were constructed so that alternative sets could be fitted, the cables for these and the sets themselves being stowed in special containers when not in use. Practically all radar equipment was heavy but delicate and required special rubber mountings to prevent damage both on the ground and in the air. Those responsible for designing the fitments had to bear in mind, in addition to the normal requirements of strength and lightness, the necessity for using materials which could be readily obtained. The maximum use had to be made of standard AGS parts and the designs had to be such that the parts could be jig-built in quantity, within the machine tool capacity of the general engineering sections concerned.

Installation under restricted working conditions became a major problem. With a flow rate of up to three aircraft per day and man-hours running into four figures, pre-production planning necessarily became very detailed. The number of aircraft of a particular type which could be accommodated on any one production line was limited to the hangar space available, even when the line continued through more than one hangar. It became, necessary to break the installation down into smaller stages by trades, in order to prevent two tradesmen requiring to be in the same place at the same time, and this was further eased by the use of night shifts. Small gangs of tradesmen, specialising in each stage, fell back down the production line as it moved forward, leave, sickness, or 'boosting' of particular stages being covered by training personnel in all stages appropriate to their trade. The output of new aircraft from parent firms fluctuated, especially during bad weather, and this, together with a shortage of operational equipment which often required extensive laboratory adjustment to make it serviceable, made it very difficult to prevent subsequent gaps in the flow of completed aircraft

Connector sets for these installations became very complicated, taking many man-hours to makeup and install. Eventually it became possible to incorporate some of these during the construction of the aircraft at the civilian constructors. This, however, proved to be a false economy as faults due to bad workmanship often did not show up until final test and the Service units requested that they be allowed to continue to fit them themselves as before. This type of trouble was frequently experienced when equipment was passed back to civilian contractors for earlier embodiment, despite detailed instructions as to the best methods, difficulties, etc., being provided. When the fitment of operational equipment was completed, the aircraft were ground and air tested and were ready for delivery to operational squadrons.

The demand for aircraft fitted with this new equipment, at one period, was so great that squadron aircrew were flown to the units to pick up their aircraft, which were sometimes used on operations the same night.

During 1944, 978 major installations were effected in Bomber Command aircraft as compared with 625 during 1943; much of the work being done in aircraft which became part of the main bomber force. Even greater versatility was required to deal with the varying and very complicated commitments for the Pathfinder force [No 8 Group] and for the Radio Countermeasures Group [No 100 Group]. Other installations in Lancaster aircraft included apparatus for jamming enemy radar equipment, particularly in connection with 'D' Day operations.

Installations for Coastal Command played an important part in the U-boat battle, particularly noteworthy being the continuous installation of antisubmarine radar devices. During the year, 168 Wellington and 26 Halifax aircraft were dealt with. These installations called for considerable backing from other sections of the Group, since in addition to the manufacture of the usual brackets, clips, platforms and harness inseparable from the installation of radar equipment in aircraft, a large amount of precision engineering was involved in the manufacture to very close tolerances of special components.

Work was also carried out in developing the radar installation aspect of a Flying Boat Station at Uig Bay. A special laboratory was installed and the first few Sunderland flying boats were fitted with anti-submarine radar before the station was handed over to No 41 Group.

Throughout 1943, No 43 Group radar installation organisation gave very close support to Fighter Command and during that year 655 night fighter aircraft were fitted with special radar devices. In the following year a further 714 aircraft were installed with both British and American radar equipment, including 415 Mosquitos for defensive and offensive roles.

A considerable portion of the available radar installation capacity was devoted to AEAF aircraft, special installations being carried out on a 'crash' basis immediately prior to 'D' Day operations, for which 430 Dakota aircraft were fitted with radar navigational aids. This was work of high priority and 200 aircraft were completed in one month alone by installation parties on operational airfields. Similar navigational aids were fitted to Albemarle and Halifax aircraft, also for AEAF

A commitment carried out on behalf of the Royal Navy was that of converting 15 Anson aircraft into flying radar classrooms for training personnel in centimetre technique. In addition, 10 Firefly aircraft were fitted with offensive radar equipment for employment as night fighters on anti-submarine patrol, this development being carried out in close liaison with Fairey Aviation Co.

Beaufighters, Mosquitos, Wellingtons, Sunderlands, Catalinas, Fortresses, and Halifax aircraft to the number of 635 were fitted with radio altimeters, most of the kits being manufactured within the Group. Various other installations to small numbers of aircraft required for special missions were also completed at short notice on behalf of numerous authorities.

A complete section of one Service repair depot was devoted to the preparation and installation of all mobile and transportable ground radar installations, to meet the requirements of the Director of Radar. At the end of 1944 320 self-contained mobile, and 720 transportable ground radar installations had been prepared and shipped to the three Fighting Services and the Allied nations. This task involved the turnover of 1,323 vehicles and 8,300 tons of radar equipment, including 21 different types of specialist vehicles and a very large variety of technical equipment.

During the early part of the year 2nd TAF and USAAF were supplied with 200 of the most modern radar convoys, complete with waterproofing kits for all vehicles. The radio section at the unit carried out the research and development of these kits, which enabled the vehicles to wade, under power, through 4 ft 6 in. of sea water. Three complete Air Transportable GCI Stations, capable of being carried in three Dakota aircraft, were designed, completed and shipped within five weeks to fulfil an urgent operational requirement shortly after 'D' Day.

Towards the end of the year considerable work was carried out on the tropicalisation of technical equipment for incorporation in Air Transportable Radar Installations.

(e) Electrics and Instruments

1944 saw a steady increase in the range and volume of electrical and instrument repair and manufacture. The introduction into the Service of new and improved devices relevant to navigation, gunnery and bombing increased not only the capacity but also the technical requirements.

In addition to these activities at repair depots, there was an increased demand for travelling parties for fitting such devices as gyro gunsights and new-type bombsights to a wide variety of aircraft Installation work took personnel to all parts of the United Kingdom and even as far as Gibraltar and the continent of Europe.

The repair of electrical equipment at units showed a marked increase over the preceding year, reaching a total of 92,000 separate items. In addition, 88,000 sparking plugs were repaired and 2,441,000 broken down, 52,314 oz. of precious metal being reclaimed. Repairs were performed in magnetos and starters, armatures, voltage regulators, suppressors, booster coils, complete ignition harnesses, bomb-distributors, electro-magnetic release and fusing units, switch boxes and innumerable other items. The capacity for re-winding starter and magneto armatures increased by 10 per cent. The high standard of workmanship required for this class of repair and the complicated processes for building up new commutators, baking and impregnating, were developed progressively.

The de-magnetisation of aircraft was taken over from RAE., Farnborough, in April 1944 and 68 aircraft were dealt with during the year.

Accumulator reconditioning was typical of numerous unspectacular activities and the number dealt with in this year was 9,238.

Manufacturing capacity became available from time to time for miscellaneous electrical equipment and was extensively used, particularly by Bomber Command, for the modification of such items as bomb-distributors, the fabrication of components for transmitters, assembly of test sets, etc.

The repair of instruments was greatly influenced by the introduction of more complicated equipment such as distant-reading compasses, air mileage units, ground position indicators, gyro gunsights and new-type bombsights. Due to the changing requirements for different types of instruments, the instrument repair sections had to maintain a high degree of flexibility. During 1944 priority was mainly allocated to navigational instruments, bombsights, gyroscopic instruments and automatic pilots. The output of navigational instruments alone was 2,230 whilst the output of 6,315 gyroscopic instruments represented an increase of more than 50 per cent. The number of automatic pilots and components dealt with amounted to 22,727.

Instrument installation in aircraft was intimately connected with operations, such commitments extending outside Great Britain to Iceland and the Middle East. As a typical instance, a special duty Lancaster squadron needed a bombsight suitable for use when attacking small targets with 12,000 lb. bombs. The contractor was unable to undertake this installation and the work was carried out by No 43 Group. It was subsequently successfully used by Bomber Command in their attack which culminated in the sinking of the German battleship Tirftitz.

Another good example of installation party activities in assisting the operational Commands in an emergency was that of the retrospective modification of 1,200 Mark VIII automatic pilots. These developed a serious fault which was endangering life, and the parties located the faulty instruments, removed, modified and re-installed them, all within a month.

In addition to completing 4,589 installations, these travelling parties gave assistance and guidance to both air and ground crews on the equipment installed. They were also able to produce valuable data, which in time led to the improvement of the equipment, both in design and function. Much of the work was carried out at very short notice and was always arranged so as to give the minimum loss in operational serviceability.

(f) Armament

The No 43 Group repair depots overhauled, repaired and modified power and manually operated gun turrets, bomb-carriers, cannons, machine guns and rocket projectors. They also repaired miscellaneous airborne offensive equipment, small arms and accessories of all types.

The repairs to turrets covered the complete range of British and American operational types, as well as training turrets and those fitted to RAF marine craft Work on American types was complicated by lack of schedules, tools and test equipment which had to be produced under local arrangements. For the major part of 1944 No 43 Group was the only available repair capacity for American turrets, and when eventually additional civilian capacity was found the Group's schedules were made available for their use. During the year 87 American and 1,480 British turrets were repaired and a further 1,250 turrets of all types were broken down for the recovery of components. Eight thousand of these components were repaired, tested and returned to the Service.

Special work in connection with repair was carried out in the Turret Repair Development Section. This section was responsible for the design and development of certain ground equipment such as six demonstration trolleys used for training RAF personnel in the operation and maintenance of various types of turrets.

The repair of weapons covered a variety of types from the 40 mm. 'S' gun to the Sten Carbine, although the chief commitments were the .303" Browning and 20 mm. Hispano guns and accessories. Repairs included 24,220 machine guns, 19,782 bomb-carriers, 3,647 cannons, 8,204 small arms and 7,950 belt feed mechanisms.

On numerous occasions the Group was called upon to fulfil tasks which for various reasons could not be done elsewhere. An instance of one such special commitment was the Sunderland flying boat front turret conversion. Due to the forward fire power of the Sunderland being inadequate, U-boats tended to stay on the surface when attacked and fight things out. An enterprising Coastal Command squadron improvised a local modification to a Wellington turret and fitted it in place of the one normally used. This proved so successful that the modification was passed to one of the repair depots in No 43 Group. Here the original mock-up was drastically altered, major structural alterations were made and the single-gun turret was converted into one with two guns. Three hundred of these modified turrets were supplied in 1944, both to the Sunderland production line and for retrospective fitting in Coastal Command aircraft

Early in 1944 Bomber Command requested a power-operated bomb winch in place of the manual winches in use at that time. A scheme was devised in which a Vane oil motor was fitted to a standard gyral winch, power being supplied by coupling to a turret training stand. By early July, 150 of these modifications had been carried out by the Group in addition to the manufacture of the necessary test equipment for the use of AID.

Another example of the way in which the armament section of the Group was able to make a direct contribution to the operational Command's effort, may be seen in the modification to the belt feed mechanism of the 20 mm Hispano gun. An inherent fault in the design was giving rise to failures under operational conditions. It was decided to fit an additional sprocket in the feed mechanism, and to effect it rapidly jigs and tools had to be designed for the purpose. The target figure of 200 mechanisms per week was reached and retrospective modification to all belt feed mechanisms completed to a total of 7,500. Close liaison was maintained with BSA who were also engaged on the modification.

(g) Synthetic Trainers

No 43 Group were responsible for the repair, overhaul and modification of the majority of synthetic trainers used in the Royal Air Force. Their responsibilities extended as far as Iceland, Gibraltar and the continent of Europe. Considerable versatility was required by personnel engaged on this maintenance work as they needed to be familiar with both the principles of the apparatus being simulated and the artificial methods of simulation. The number of different types of trainers varied and included Link, Night Vision, AM Bombing, Dome AA., Edmunds Deflection, Silloth, Celestial Navigation, Turret Gun Sighting, Standard Free Gunnery (with gyro gunsight or trace simulator), Low-Level Bombsight, Fisher Front Gun, Spotlight trainers and Radar trainers types 19, 54, 549 and 70.

The Link trainer was the largest single commitment during 1944, 575 were overhauled, 2,327 serviced and 1,168 installed or transferred. The figures for the previous year were 231, 1,843 and 522 respectively. In addition, 321 of the latest type of Link trainers from America were overhauled and modified to suit British instruments.

An interesting manufacturing commitment was the Turret Manipulation Assessor which originated in Flying Training Command and was prototyped at a No 43 Group unit. This proved successful and work commenced on the bulk manufacture of 300 Assessors.

Synthetic trainers and day-to-day operations are not readily associated, but instances of such liaison did occur. One example was the manufacture for 2nd TAF of a mobile Link trainer. The prototype was completed within 15 days and included a sound-proof power supply and air conditioning. This trainer proved to be most satisfactory and a number were subsequently built.

(h) Marine Repair

Responsibility for all repair, overhaul and modification beyond user-unit capacity, of RAF marine craft operated from the United Kingdom and the continent of Europe rested with No 43 Group. Five Marine Craft Repair Units were devoted solely to this work. Craft dealt with ranged in size from 10 ft flare path dinghies to 73 ft high-speed air/sea rescue launches. In addition to repair to marine craft directly connected with aircraft, a number of seaplane tenders and marine tenders were repaired for Balloon Command who used them to tend floating balloon barrages. All craft being sent overseas were passed through a Marine Craft Repair Unit to ensure that they were fully serviceable prior to shipment and this necessitated working to a strict time-table to meet sailing dates. Repairs were also carried out to motor torpedo boats and motor gun boats at the special request of the Royal Navy. Concurrently with the repair and overhaul of a wide variety of craft the specialist equipment fitted therein had also to be dealt with, thus Marine Craft Repair Units had a variety of activities covering a wide range of trades.

Special repair facilities were organised in connection with the liberation of NW Europe. This involved the formation of three additional repair bases on the south coast and attachment of a RAF repair party to a naval depot ship to carry out emergency repairs to marine craft in the landing area. During this period over 100 high-speed launches were stationed between Great Yarmouth and Lands End. Work continued day and night during the three months that this scheme was in operation and a serviceability of over 90 per cent was maintained. A total of 438 repairs was carried out, often in bad weather and with the added difficulty of avoiding flying bombs. Later in the year countermeasures against U-boats in the northern approaches resulted in an increase in the air/sea rescue craft stationed in this area and a special organisation was set up for their emergency repair and overhaul.

Altogether a total of 1,574 craft were repaired during the year and 60 per cent these were high-speed launches. This represented a monthly output of 137 aft as compared with 83 craft per month in 1943.

The safety of flying boats and RAF marine craft depended upon the efficiency of the mooring equipment. A special section of one unit was allocated this work which also included target moorings and equipment, chain cable, buoys and anchors. Nearly 1,000 tons of mooring material were used during the war and it also became necessary to repair bombing targets at 3-6 monthly intervals instead of the 12-18 months which had sufficed in the earlier phases of the war.

(I) Other Activities

The activities of No 43 Group were so wide that it is impracticable to include them all but there were, however, certain other commitments which should be mentioned. Perhaps the most noteworthy were the general engineering sections which formed the hub around which all other activities revolved.

The general engineering sections were equipped to carry out all the usual basic engineering processes. They comprised fully equipped machine shops (the largest of which covered over 35,000 sq ft), general fitting, carpenters', blacksmiths' and metal workers' shops. Facilities were available for press work, welding, cutting, heat treatment, sand and shot-blasting, electro-deposition of nickel, chromium, copper, zinc, cadmium, lead, tin and silver, metal spraying, painting and fabric work. Three of the units had foundries for casting brass, iron and light alloys and were also equipped with plants for the anodic treatment of aluminium alloys.

The primary function of the GESs was to cover the basic engineering needs of the other sections already described. In addition, a continuous flow of manufacture and modification work was accepted from various sources such as MAP, AM, operational Commands, USAAF, Admiralty and civilian contractors. This work included the design, development and construction of prototypes of various tools, jigs, test-rigs, etc., which were often required at very short notice. Much of the work consisted of manufacturing modifications for the operational Commands pending their incorporation by contractors during production, and when the supplies of spares and tools for American aircraft were delayed the sections 'filled the breach.'

Among the equipment manufactured over a period of twelve months, by one unit alone, were included more than 36,000 items for Bomber Command, 1,800 for Coastal Command, 3,000 for Flying Training Command, 1,400 for Transport Command, 1,700 for the USAAF, and 16,000 for civilian firms - a grand total of 60,000 items. Additional work was also carried out for other formations.

The repair of barrage balloons was a normal commitment of No 43 Group, but during the height of the flying bomb attacks on the United Kingdom this work was stepped up. During 1944, 2,011 balloons were repaired as against 1,442 for the previous year. An additional commitment was the modification and test of American balloons for use in this country and the target of 60 balloons per week was achieved and maintained until the necessity no longer existed.

Parachute repair and packing was undertaken at four units within the Group and they became the leading authority for repair of such items of safety equipment. Throughout the year 22,394 parachutes, 3,757 items of associated airborne equipment and 3,746 aircraft dinghies were repaired.

The repair of the clusters of 60-ft canopies used for dropping airborne equipment was also their responsibility.

There were four motor transport sections in the Group which carried out complete overhaul, major repairs and 10,000-mile inspections of MT vehicles. The Repair and Salvage Units of No 43 Group were the largest users of MT and a special capacity was allocated to cover their expected arisings from the ration of NW Europe. In addition, repairs were carried out to a variety specialised vehicles over and above urgent conversion work for Balloon Command.

The repair and replenishment of oxygen cylinders amounted to over 134,000 the year. A development section was set up and work carried out to increase the output of oxygen producing plants. Two prototype mobile producing plants were constructed. These weighed eight tons each and were designed so that they could be dismantled in three hours, for transportation by air, and assembled at their destination in nine hours. Other work on gaseous apparatus included the test, modification and equipping to schedule of 174 new mobile plants as well as major servicing of 30 plants by travelling parties.

Salvage and Repair on Site

Salvage

At the beginning of the war it was realised that the repair of crashed aircraft would play a vital part, second only to new production, in keeping the operational units supplied with the aircraft they needed. A salvage organisation was formed for the collection and delivery to repairers of all repairable aircraft or components, and for removal to salvage dumps those which were beyond economical repair. It was also expected to deal with any aircraft which required to be dismantled or removed. Its primary concern, however, was the the movement of damaged aircraft which could not be repaired on site or were total losses. The tern salvage as used by No 43 Group meant very much more than what is implied by the popular use of the word, and the function of the salvage organisation could perhaps better be described as removal and recovery. It included within its scope the whole of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

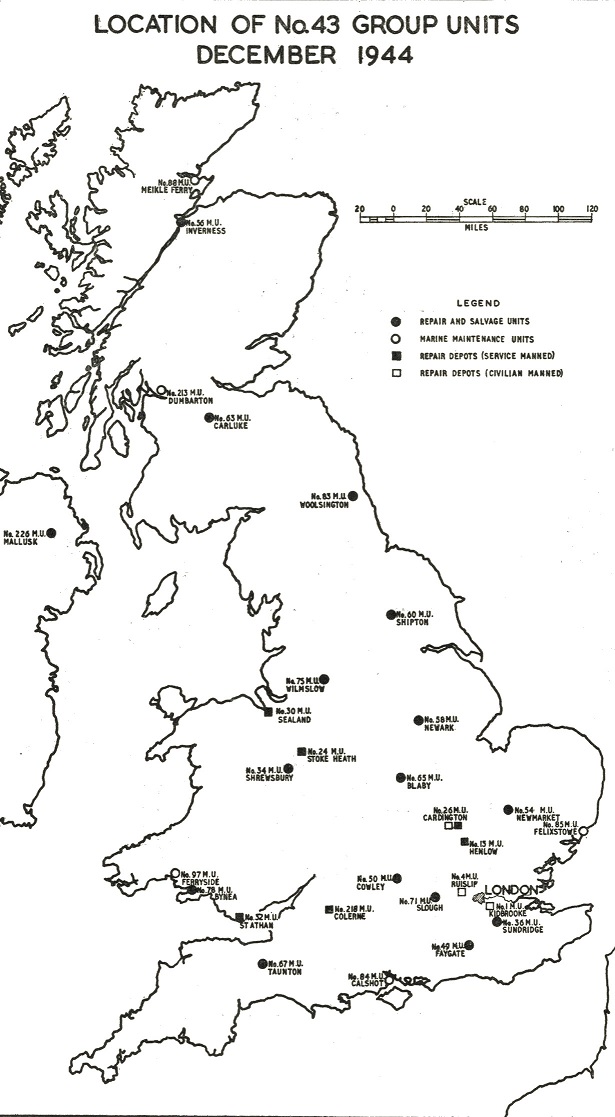

For the purpose of salvage the country was divided into sixteen areas each served by one Repair and Salvage Unit. The areas in which a small number of crashes was expected were naturally larger than those with a high anticipated crash incidence, and they varied in size from 14,000 square miles in Scotland to 400 square miles in Kent. Nevertheless the work was still uneven and the the of the RSUs varied from an establishment of 250 to one of 1,500. Flexibility in dealing with a sudden pressure of work in one area was maintained by a centralised control which directed reinforcements of personnel and transport from one area to another.

No provision had been made for this activity in peace-time so that when war broke out the units had to be accommodated wherever space was available. Personnel of these units were billeted out, except in those few cases where it was possible to take over existing RAF stations. Lack of planned accommodation as therefore one of the difficulties which the RSUs had to overcome.

The detailed procedure for the removal and recovery of crashed aircraft was laid down in Air Publication 1921, and in so far as it affected No 43 Group, in HQ, No 43 Group Salvage Staff Instructions, it is sufficient to state that all crashes within the United Kingdom and those of aircraft based in the United Kingdom were reported to No 43 Group by a standardised crash signal (over 127,000 were reported up to the end of March 1945). The category of a damaged aircraft was decided by a crash inspector and if this category was 'B' or 'E' its removal to its appropriate destination was carried out by the salvage organisation of No 43 Group.

The figure of 31,668 aircraft so categorised in 1944 is formidable, but to appreciate fully its significance some account must be taken of the difficulties involved. The majority of crashes naturally took place on or near an airfield; but others were on seashores, mountain sides, in bogs, moors and fens, sometimes miles from the nearest road. Others crashed on railways and thoroughfares where speed of removal became the most important factor.

Special techniques were developed for dealing with awkward crashes from difficult terrain and special road transport, fitting and loading tackle, all of which were non-existent at the beginning of the war, were designed for this purpose. Some idea of the transport involved can be gathered from the fact that no fewer than six 60-ft articulated vehicles were required for the movement of one four-engined bomber.

When the USAAF first joined in operations its repair and maintenance organisation was undeveloped, so that the responsibility for the salvage of all American aircraft fell upon No 43 Group. Eventually the Americans developed their own organisation for this purpose but the proviso remained that No 43 Group undertook salvage for them on request, and, in fact, over 1,400 American aircraft were so salvaged dining 1944.

The salvage organisation was also responsible during the war for the assessment of damage to private property caused by all the crashes and subsequent salvaging operations, and also for the settlement of the resulting claims. Over 6,000 such claims were made in 1944 and over £270,000 paid out.

With the liberation of NW Europe in 1944 some of the operational bases moved to the Continent, bringing fresh responsibilities.

Not only did mobile salvage and repair-on-site parties belonging to No 43 Group assist the 2nd Tactical Air Force on the Continent, but also an important commitment was accepted for retrieving from the Continent repairable aircraft, equipment and MT. The Salvage Ferry Service, as it was called, originally operated between Le Tréport and Gosport by LCTs and considerable difficulties had to be overcome in loading and unloading the long, low loaders on to and off these craft. Later the service was organised between Calais and Dover by train ferry and between Antwerp and Tilbury by MT ship, and the original route was discontinued. Shipments commenced at the beginning of July 1944, and by March 1945 over 1,000 aircraft had been delivered to repairers in the United Kingdom.

(b) Repair on Site

The repair of Category' AC 'aircraft, that is, aircraft which could be repaired on site but which were beyond the capacity of the holding unit to repair, was originally carried out by civilian contractors. Early in 1943 the scope of the salvage organisation was extended to include this work, the aim being to provide training for Service personnel, to release civilians for work on new production, and to avoid the expense and accommodation difficulties involved in the use of civilian repair gangs.

The Repair and Salvage Units thus had the two clearly distinct functions of repair on site and salvage, and were organised accordingly in two separate sections under one chief technical officer.

The number of aircraft repaired on site and returned to the Service by No 43 Group units in 1944 was 3,687. Later, certain types of aircraft were repaired on site only by the RSUs, others only by civilian contractors, whilst a third class were repaired by either, according to convenience or repair capacity. The proportion of Category 'AC' aircraft dealt with by No 43 Group steadily increased and by early 1945 represented more than one third of the total. No 43 Group were responsible for progressing all repair work done by civilian contractors and for engine changing on all aircraft repaired on site.

A feature which differentiated repair on site from the salvage work of the RSUs was that whereas the latter was organised on a territorial basis, repair on site was divided according to types of aircraft, certain units specialising in certain types. Thus when an aircraft was categorised as repairable on site it became the responsibility of the nearest RSU specialising in that type of aircraft. This policy was dictated by the necessity for effecting economy in the holding of equipment and spares and by the need to take full advantage of specialised knowledge and experience of a particular type.

In certain cases as, for instance, at aerodromes with emergency landing grounds, where heavy arisings of repair were expected of certain types of aircraft not within the scope of the local RSU, a permanent detachment was made from the appropriate RSU

The aim throughout was to achieve the greatest possible mobility for repair-on-site parties and for the Salvage gangs. During the liberation of NW Europe these parties were sent to the Continent in support of 2nd TAF and were provided with mobile workshops and, where necessary, with. caravans for living quarters, so that they could function as mobile independent units.'

Allocation of Equipment for Repair

Some reference to this has already been made throughout the text but a summary of the method by which the input of work to civilian factories and Service units was regulated gives a clearer picture of this aspect.

Aircraft - No 43 Group salvage organisation was responsible for the collection of aircraft requiring repair. HQ, No 43 Group was kept fully informed by the Civilian Repair Organisation as to the capacity of all civilian repairers and made the distribution to civilian or Service units accordingly.

|

| Diagram 9 |

Aero and Marine Craft Engines - The Directorate of Repair and Maintenance allotted engines for repair or overhaul to the civilian or Service repairers in accordance with the available capacity. Air Ministry was kept informed of all movements so that engines, when completed, could be returned to Service as and when required.

Mechanical Transport - The Air Ministry made allocations in accordance with the repair capacity notified to them by the Civilian Repair Organisation and by the Service Repair Depots of No 43 Group. Air Ministry was also informed when repair was complete, so that the vehicles could be returned to service as required.

Marine Craft - No 43 Group arranged either for the movement of the craft in question to one of the Marine Maintenance Units or alternatively sent out a repair-on-site working party.

The distribution of repairable equipment other than that mentioned above was regulated in detail in accordance with AMO A.736/43. From this it will be seen that a small proportion of items was despatched direct to civilian repairers but the bulk of the equipment went to a central collecting depot, of which there were nine, each specialising in a particular range of equipment. They were known as Repairable Equipment Units or Depots, and here the equipment was surveyed, classified and issued to repair units or contractors. Three of these REDs, Nos. 1, 2 and 3, were controlled by the Directorate General of Repair and Maintenance and were administered by the Civilian Repair Organisation (CRO). Their output was regulated jointly by the CRO and No 43 Group in order to maintain a correct balance of distribution between repair units of No 43 Group and civilian repairers. The remaining six were known as Repairable Equipment Units and were administered by No 43 Group under the technical control of DGRM, their location being at one or other of the Service Repair Depots.

The Output of Aircraft Repaired by the Civilian Repair Organisation, 1940 to 19451

The work of repairing crashed aircraft by the Civilian Repair Organisation for the Director General of Repair and Maintenance at the Ministry of Aircraft Production was similar to that performed by No 43 Group.

Diagram 10

Yearly Summary of the Output of Aircraft repaired by the Civilian Repair Organisation

| Year | Week Ending | Output of Repaired Aircraft | ||

| At Works | On Site |

Total |

||

| 1940 | 2 Mar - 25 May | Not Available | Not Available | 252 |

| 1 Jun - 28 Aug | Not Available | Not Available | 1,658 | |

| 31 Aug - 28 Dec | 1,912 | 1,130 | 3.042 | |

| 1941 | 1 Jan - 27 Dec | 6,540 | 7.013 | 13,553 |

| 1942 | 3 Jan - 26 Dec | 7,695 | 8,979 | 16,674 |

| 1943 | 2 Jan - 25 Dec | 8,176 | 9,945 | 18,121 |

| 1944 | 1 Jan - 30 Dec | 8,213 | 10,869 | 19,082 |

| 1945 | 6 Jan - 3 Aug | 3,764 | 4,520 | 8,284 |

| Total | 80,666 | |||

This page was last updated on 08/07/19